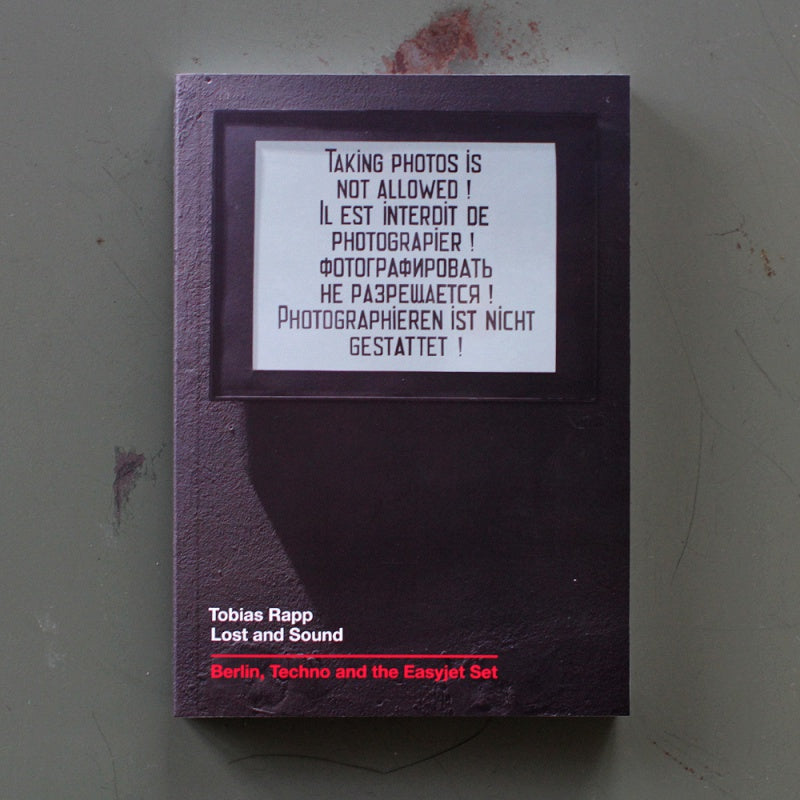

Lost and Sound

Lost and Sound

Almost everyone in the world knows someone who has flown to the German capital in recent years and proudly returned with bizarre stories of previously unimagined highs at endless techno parties at Berghain, Watergate or Tresor. All these stories contain a grain of truth.

But many questions remain unanswered: Why is it that thousands of clubbing tourists land at Berlin Schönefeld airport every weekend? Why have clubs like Berghain become the stuff of legend the world over? Why have some of the best-known producers and techno DJs like Richie Hawtin and DJ Hell moved with their labels to this city?

These are the kind of questions explored in Lost and Sound by Tobias Rapp, a German music journalist who has been living, working and partying in Berlin since the beginning of the nineties. He has spoken with DJs, clubbers, label bosses, hostel managers and urban planners; he has looked and listened carefully; and most important of all, he has been part of the dance floor himself. Following its publication in Germany in February 2009, Lost and Sound made an impact not seen from a book about popular music for a long time. Originally published by the renowned Suhrkamp Verlag, which also manages the works of Brecht, Adorno and Benjamin, the book almost single-handedly brought techno back into the eyes of the German media. Suddenly everyone wanted to get on board again. In the spring and summer of 2009 all the German daily and weekly papers carried reports on the Berlin party scene. It was around this time that Rapp switched employers.

Germany’s best-selling news magazine Der Spiegel appointed him as its new pop music editor a few months ago. As far as music journalism in Germany is concerned, there are few higher rungs on the ladder. Lost and Sound was simply crying out to be translated into English. Aside from the fact that English is the lingua franca of techno culture, the majority of the people that this book is about – producers, DJs, tourists – hardly speak German. But these are the people responsible for the altogether more pleasant associations Berlin now triggers – after ‘Hitler’s city’ and ‘the walled city’ comes ‘the party city’. It is these people who cultivate Berlin’s spirit of excess, along with the other groups which make up the Berlin clubbing demographic: the gay community, the East Germans (known as ‘Ossis’) and the offspring of middle-class West Germans. It is they who roam Berlin’s new club mile, from Schlesisches Tor to Alexanderplatz, turning night into day and day back into night. And it is they who have prompted some local journalists to speak of Berlin as a kind of a metropolitan Ibiza, a party Mecca on constant overdrive on the banks of the Spree. But Ibiza is a wholly inappropriate point of reference.

As Rapp shows in Lost and Sound, the mechanisms of commercialisation and displacement which have long-since turned the Spanish island into a tourist nightmare have made little mark on Berlin. Fortunately, it has retained an indomitable spirit of creative cooperation and coexistence. The city still has great pulling power. Anyone who reads Lost and Sound will feel the same compulsion to hop on a plane and join Berlin – as Rapp did – for a week of raving.

But many questions remain unanswered: Why is it that thousands of clubbing tourists land at Berlin Schönefeld airport every weekend? Why have clubs like Berghain become the stuff of legend the world over? Why have some of the best-known producers and techno DJs like Richie Hawtin and DJ Hell moved with their labels to this city?

These are the kind of questions explored in Lost and Sound by Tobias Rapp, a German music journalist who has been living, working and partying in Berlin since the beginning of the nineties. He has spoken with DJs, clubbers, label bosses, hostel managers and urban planners; he has looked and listened carefully; and most important of all, he has been part of the dance floor himself. Following its publication in Germany in February 2009, Lost and Sound made an impact not seen from a book about popular music for a long time. Originally published by the renowned Suhrkamp Verlag, which also manages the works of Brecht, Adorno and Benjamin, the book almost single-handedly brought techno back into the eyes of the German media. Suddenly everyone wanted to get on board again. In the spring and summer of 2009 all the German daily and weekly papers carried reports on the Berlin party scene. It was around this time that Rapp switched employers.

Germany’s best-selling news magazine Der Spiegel appointed him as its new pop music editor a few months ago. As far as music journalism in Germany is concerned, there are few higher rungs on the ladder. Lost and Sound was simply crying out to be translated into English. Aside from the fact that English is the lingua franca of techno culture, the majority of the people that this book is about – producers, DJs, tourists – hardly speak German. But these are the people responsible for the altogether more pleasant associations Berlin now triggers – after ‘Hitler’s city’ and ‘the walled city’ comes ‘the party city’. It is these people who cultivate Berlin’s spirit of excess, along with the other groups which make up the Berlin clubbing demographic: the gay community, the East Germans (known as ‘Ossis’) and the offspring of middle-class West Germans. It is they who roam Berlin’s new club mile, from Schlesisches Tor to Alexanderplatz, turning night into day and day back into night. And it is they who have prompted some local journalists to speak of Berlin as a kind of a metropolitan Ibiza, a party Mecca on constant overdrive on the banks of the Spree. But Ibiza is a wholly inappropriate point of reference.

As Rapp shows in Lost and Sound, the mechanisms of commercialisation and displacement which have long-since turned the Spanish island into a tourist nightmare have made little mark on Berlin. Fortunately, it has retained an indomitable spirit of creative cooperation and coexistence. The city still has great pulling power. Anyone who reads Lost and Sound will feel the same compulsion to hop on a plane and join Berlin – as Rapp did – for a week of raving.

Regular price

€10,00

€10,00

/

VAT included.

Almost everyone in the world knows someone who has flown to the German capital in recent years and proudly returned with bizarre stories of previously unimagined highs at endless techno parties at Berghain, Watergate or Tresor. All these stories contain a grain of truth.

But many questions remain unanswered: Why is it that thousands of clubbing tourists land at Berlin Schönefeld airport every weekend? Why have clubs like Berghain become the stuff of legend the world over? Why have some of the best-known producers and techno DJs like Richie Hawtin and DJ Hell moved with their labels to this city?

These are the kind of questions explored in Lost and Sound by Tobias Rapp, a German music journalist who has been living, working and partying in Berlin since the beginning of the nineties. He has spoken with DJs, clubbers, label bosses, hostel managers and urban planners; he has looked and listened carefully; and most important of all, he has been part of the dance floor himself. Following its publication in Germany in February 2009, Lost and Sound made an impact not seen from a book about popular music for a long time. Originally published by the renowned Suhrkamp Verlag, which also manages the works of Brecht, Adorno and Benjamin, the book almost single-handedly brought techno back into the eyes of the German media. Suddenly everyone wanted to get on board again. In the spring and summer of 2009 all the German daily and weekly papers carried reports on the Berlin party scene. It was around this time that Rapp switched employers.

Germany’s best-selling news magazine Der Spiegel appointed him as its new pop music editor a few months ago. As far as music journalism in Germany is concerned, there are few higher rungs on the ladder. Lost and Sound was simply crying out to be translated into English. Aside from the fact that English is the lingua franca of techno culture, the majority of the people that this book is about – producers, DJs, tourists – hardly speak German. But these are the people responsible for the altogether more pleasant associations Berlin now triggers – after ‘Hitler’s city’ and ‘the walled city’ comes ‘the party city’. It is these people who cultivate Berlin’s spirit of excess, along with the other groups which make up the Berlin clubbing demographic: the gay community, the East Germans (known as ‘Ossis’) and the offspring of middle-class West Germans. It is they who roam Berlin’s new club mile, from Schlesisches Tor to Alexanderplatz, turning night into day and day back into night. And it is they who have prompted some local journalists to speak of Berlin as a kind of a metropolitan Ibiza, a party Mecca on constant overdrive on the banks of the Spree. But Ibiza is a wholly inappropriate point of reference.

As Rapp shows in Lost and Sound, the mechanisms of commercialisation and displacement which have long-since turned the Spanish island into a tourist nightmare have made little mark on Berlin. Fortunately, it has retained an indomitable spirit of creative cooperation and coexistence. The city still has great pulling power. Anyone who reads Lost and Sound will feel the same compulsion to hop on a plane and join Berlin – as Rapp did – for a week of raving.

But many questions remain unanswered: Why is it that thousands of clubbing tourists land at Berlin Schönefeld airport every weekend? Why have clubs like Berghain become the stuff of legend the world over? Why have some of the best-known producers and techno DJs like Richie Hawtin and DJ Hell moved with their labels to this city?

These are the kind of questions explored in Lost and Sound by Tobias Rapp, a German music journalist who has been living, working and partying in Berlin since the beginning of the nineties. He has spoken with DJs, clubbers, label bosses, hostel managers and urban planners; he has looked and listened carefully; and most important of all, he has been part of the dance floor himself. Following its publication in Germany in February 2009, Lost and Sound made an impact not seen from a book about popular music for a long time. Originally published by the renowned Suhrkamp Verlag, which also manages the works of Brecht, Adorno and Benjamin, the book almost single-handedly brought techno back into the eyes of the German media. Suddenly everyone wanted to get on board again. In the spring and summer of 2009 all the German daily and weekly papers carried reports on the Berlin party scene. It was around this time that Rapp switched employers.

Germany’s best-selling news magazine Der Spiegel appointed him as its new pop music editor a few months ago. As far as music journalism in Germany is concerned, there are few higher rungs on the ladder. Lost and Sound was simply crying out to be translated into English. Aside from the fact that English is the lingua franca of techno culture, the majority of the people that this book is about – producers, DJs, tourists – hardly speak German. But these are the people responsible for the altogether more pleasant associations Berlin now triggers – after ‘Hitler’s city’ and ‘the walled city’ comes ‘the party city’. It is these people who cultivate Berlin’s spirit of excess, along with the other groups which make up the Berlin clubbing demographic: the gay community, the East Germans (known as ‘Ossis’) and the offspring of middle-class West Germans. It is they who roam Berlin’s new club mile, from Schlesisches Tor to Alexanderplatz, turning night into day and day back into night. And it is they who have prompted some local journalists to speak of Berlin as a kind of a metropolitan Ibiza, a party Mecca on constant overdrive on the banks of the Spree. But Ibiza is a wholly inappropriate point of reference.

As Rapp shows in Lost and Sound, the mechanisms of commercialisation and displacement which have long-since turned the Spanish island into a tourist nightmare have made little mark on Berlin. Fortunately, it has retained an indomitable spirit of creative cooperation and coexistence. The city still has great pulling power. Anyone who reads Lost and Sound will feel the same compulsion to hop on a plane and join Berlin – as Rapp did – for a week of raving.